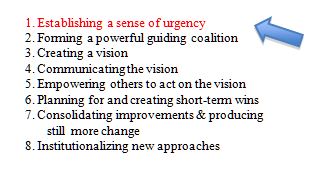

If you’re reading this, chances are you are a sustainability leader or champion within your company. Chances are, also, that that you still face resistance getting some of your colleagues on-board. In my previous article, “Putting the Management Back in Change”, I posited that companies who are truly committed go beyond individual project successes to institutionalize sustainability and address intentional change efforts in their culture, operations and client services. In the business world, John Kotter’s 8 element model of organizational transformation identifies key components for success, beginning with creating a sense of urgency, which is the focus of this article (subsequent articles will address the other 7 points).

Leaders of successful firms (and their clients) know that getting a LEED portfolio under their belt does not alone make your firm “green”. The hard work to build culture, shift mindsets, adopt integrative design, and incorporate metrics – those things don’t happen by accident. They take thoughtful planning and commitment. That hard work doesn’t even get off the starting block if company leadership doesn’t recognize sustainability as a business priority, which is – unfortunately – the case in too many firms. In most cases, it’s middle management or staff even lower in the food chain that champion the cause. For those who lead from the middle, creating a sense of urgency is the pivotal moment in a long-term effort.

So how can you create a sense of urgency? What makes people care?

There are two basic approaches; one is experiential and the other is a methodical process that I call the Business Case.

The experiential approach entails having company leadership undergo a personal epiphany, one that ties to their core values and beliefs. This can be a tall order, although not impossible. A CEO of a global real estate company went to visit a friend in Greenland and saw first-hand the melting of glaciers – this caused him to chart a completely new course with the management of his company’s portfolio.

For most, the Business Case is a more likely path.

First of all, in a large company, it’s ideal to have a small group of people with a shared vision working together, especially if they represent different functions within the company (project management, IT, HR, finance). Next, there are 4 elements to consider:

- Interests: What do people care about? What keeps them up at night?

- Analysis: What data can be mined to tell a compelling story? What’s the competitive landscape?

- Influence: Who has the most influence? Whose voice will be listened to?

- External Relationships: What do clients really want? How satisfied are they now?

Interests: It’s difficult to create a sense of urgency if you don’t know what people perceive as urgent! This is where you need to let go of your own perceptions, ideas and mental models and figure out what key decision-makers care about. Is it bottom line profits? Is it being perceived as a thought-leader? Is it client opinion? Is it a design ethos? Staff retention? Instead of pushing your own ideas, step back to figure out how to link your agenda to their interests. Remember also that leadership may consist of a number of partners whose opinions on this vary. Learning what they care about is likely not as simple as a chat over coffee, but may take many conversations with both the parties in question and those who know them well.

Analysis: Analyzing the company’s current situation and competitive ranking is both about gathering data to tell a story and about bringing new information to light. Gathering external industry data about the market and trends is important so that a larger context is established. Internal and external surveys will paint a picture of how the company is perceived. If leadership cares aboutstaff retention, and a majority of folks indicate that sustainability is important to them that may be worth knowing. Many times, internal surveys reveal a lot about inconsistency and inefficiencies in staff utilization which surprises leadership, who may think that there is little wasted time. There is often a disconnect between leadership perception of capabilities and staff perception. External surveys of clients are rare and are a wealth of information.

You may need to reframe information in a new way. Let’s say bottom line profit is a driving interest. If the company has been holding its own, looking at a profit & loss statement doesn’t do much. However, if you can show that the company’s revenues in a particular market are lagging behind competitors and their ‘green’ projects, then the absolute profit number starts to be less meaningful than this previously invisible loss.

Influence: Analysis includes stakeholder mapping, understanding who has power and authority and who has influence on whom. Part of this is about building strong coalitions (which is the topic of a future article) and part of it is to get your head around whose voices are perceived by leadership as worth listening to. Creating a sense of urgency is equal parts content and delivery. The best messenger may not be you, even if you have the vision to drive the initiative!

External Relationships: Leveraging external relationships is key. Your clients and partners are a great source of information about their needs, as well as a reality check about how you are perceived. Clients may want services that you don’t know about and don’t yet provide. I have had quite a few conversations with clients who say they are not happy with green building services they are getting–which would be news to their architects and engineers, who think their clients are happy. Most importantly, long-standing, repeat clients, may be the best advocates for your interests. When internal champions who manage client relationships can engage them about sustainability and make them partners in a desired change, those very clients can be a key part of conveying an urgent message.

Let’s play this out in an example.

I was working with a project architect at a large national firm that had a healthcare practice. Although this firm marketed their position as a ‘leader in green building’, this architect gave many examples of how that wasn’t really the case, especially not in their healthcare practice in his office. He felt powerless. He had lobbied his managers, made the arguments (sometimes using their own marketing materials) and advocated for changes that he thought were critical to their business. But nothing happened. His managers did not perceive any urgency around his claims. Their business was solid and their clients were happy (so they thought).

The first thing I advised him to do was gather a small group – including marketing, finance, a project manager and another project architect. They began gathering information about the managers that they needed to engage, to understand their interests and learn whose voices were most influential. They brainstormed the current state of things that they thought their managers didn’t know and started creating a game plan to do some analysis and engage some of their clients and partners (external relationships) . They did some market research and put together a snazzy powerpoint showing the number of hospitals in the US with green building policies, LEED certified buildings, which firms had won which of those projects over the past 3 years (and what percentage was theirs). They put together some internal surveys and conducted short phone interviews with several clients. Their internal surveys showed what skills and capacities were weak and where time was being wasted on projects because of poor knowledge management. They took their best guesses at what performance they were achieving and compared that to data published about the sector. The client interviews highlighted concerns about their working relationship with engineers and the perceptions that this compromised the quality of the final project. The interviews also revealed areas where the clients would be interested in expanded services, or increased scope within contracts. Then, the group spent some time on a weekend doing post-project assessments to show how the firm could have achieved measurable improvements (and LEED certifications) if they approached projects differently and tightened up internal methodologies for design.

This effort was spread out over a number of months. Once they had gathered a file chock-full of compelling information, the question was how to convey it and what exactly they were going to propose if they were successful in engaging interest. They ended up creating an event that included some of their key clients and partners that was focused on meeting the demands of the future and the implications on healthcare. They preceded that with a briefing for leadership where they shared sensitive information and the input from key clients. At the event, leaders heard first-hand from their clients about their concerns, priorities and needs. Following the event, leadership requested a meeting to discuss business opportunities and solicited input from this group about what they would propose – which, of course, was already teed up!

The group had the right people working together to make this happen. They were able to create a compelling case using relevant information packaged well and they choreographed interactions so that those who had the most influence were voicing key messages. The urgency they conveyed addressed both weaknesses in current practice and business opportunities for the future. They were able to get a leadership level commitment to adopt some new commitments and set goals that hadn’t even been discussed before.

Not every effort is a win. Sometimes, especially when there is only one decision maker, you can make the best case for urgency and it won’t matter. The larger the ship, the harder it is to turn, but if you recognize that creating a sense of urgency is the first order, you’ll focus on things that are the most valuable for future efforts to succeed. How do you know that the urgency rate is high enough? Kotter says that when 75% of leadership is genuinely convinced that the status quo is more dangerous than change…that’s when you have a chance!

A key ingredient to success in this case was creating strong coalitions internally, and leveraging their external relationships, which is what I’ll tackle in the next article.